Fifteen years ago, I was working in the Gaza Strip with the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees in the Near East – the rather unwieldy name of the organisation better known by its acronym, UNRWA. It was a difficult, fascinating, wonderful, exciting, enjoyable, unforgettable assignment. UNRWA’s role in Palestine is unique. It was created soon after the State of Israel was unilaterally declared, a temporary agency set up to deliver services to the Palestinians who had been driven from their homes by fear, rumour or force. More than 60 years later, UNRWA is still working to its mandate. Before the Palestinian Authority (PA) was able to take over governance in the mid-1990s, UNRWA was effectively the ‘government’ of Palestine, running the schools and health clinics, even collecting the garbage.

Anyway, UNRWA’s task has always been challenging. Working for UNRWA, on the other hand, is challenging but a privilege. It does such great work and I look back on my short time with the agency as an important and memorable part of my working life. But living in Gaza in the mid-1990s was, let’s say “interesting”. There were no cinemas, no clubs or bars, only a couple of restaurants. Although there were little corner stores, there were no supermarkets, no department stores. The people who lived in Gaza used to say it was like living in a prison. The difference for me was that I could leave when I wanted to; the Palestinians in Gaza could not.

So, when the pressures of living in Gaza became too tough, I would get into my little UN car and drive to Jerusalem, where I could sip a cool drink on the terrace of a nice hotel, or visit the ancient sites of Jericho or Bethlehem, or explore the West Bank town of Ramallah, heart of the Intifada but also home to a thriving artistic community and colourful coffee shops.

Often on weekends I would stay with friends on the northern edge of Jerusalem and drive to Ramallah from their house. The route would take me along a rubble-strewn, pretty much undeveloped road, through a roadblock/checkpoint at which a couple of laid-back Israeli soldiers would check ID documents, search vehicles and ask a few questions before waving you on.

Concrete evidence

Today, 7 September 2012, I am again in Ramallah. It is a modern, thriving town, West Bank headquarters of the PA and Palestinian President Mohammad Abbas. Although the West Bank economy relies almost entirely on overseas aid, it has all the hallmarks of a place where investment is healthy. I was pleasantly surprised when I arrived.

But I was shocked by the journey here. The road from Jerusalem to Ramallah is so developed that the two towns are effectively joined together. It would be impossible to know where Jerusalem ends and Ramallah begins were it not for the Israeli checkpoint between the two. From my hotel window I can see the outer suburbs of Jerusalem rubbing shoulders with the southern edge of Ramallah.

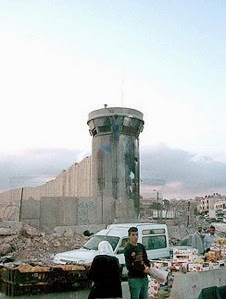

The shock, though, was the view from the car window as we drove closer to the West Bank. Where once there were views across villages and open land, now there is a high brick wall. The Wall, built by the Israeli government to encircle the West Bank, ostensibly to stop Palestinian suicide bombers from making their way into Israeli towns and settlements, is more than three times as long as the Berlin Wall was.

It is confronting, The Wall. It is shocking to anyone who celebrated the days the Berlin Wall came down, marking the end of repression in East Berlin and heralding the reunification of families long separated by the ultimate political statement, promising the freedoms to which every human has an unalienable right.

It is interesting to reflect on the different names The Wall has been given. The Israelis call it a ‘security fence’ to emphasise the military imperative they believe justifies its building and to somehow suggest a modest lightweight construction rather than the imposing concrete monstrosity it is. Official US sources write about the ‘seam’ line, erroneously suggesting that the wall joins two areas rather than splitting them apart. Human rights organisations in both Israel and Palestine talk about a ‘separation barrier’, stressing the reality of its impact on the people it affects: people separated from their workplaces, their friends and families, and from the land they claim as theirs by right.

Whatever you call it, The Wall is surely unacceptable. Many organisations have pointed out that in places it pushes beyond the ‘green line’ of the 1949 armistice and constitutes a new land grab by Israel. It is a visible demonstration of a determination to divide and conquer, to isolate and discriminate and to set in concrete – literally – an intransigent approach to the possibility of peace.

Changing times

My reaction to The Wall in these first few days of being confronted with it is quite emotional.

I first travelled in this region in the early 1970s. In those days, Israel was a land of olive groves and orchards, of pristine beaches and natural beauty. I visited a kibbutz, that quintessential symbol of commitment to building a land of hope and peace. In Israel, I met wonderful people focused on family, friends and a stable and prosperous future. In the West Bank, I sat down to eat with Palestinians dispossessed but hopeful of a just settlement that would see them once again living alongside Jewish and Christian neighbours, sharing the vital job of securing a peaceful, happy future for their children.

When I returned 20 years later, Israel had turned into a gigantic building site, the green groves nestled between uncontrolled development and overcrowding. The kibbutzim had become the enemy within, misunderstood and misrepresented. Israelis and Palestinians lived as neighbours separated by lines drawn by political processes and military aggression. Hope was hanging by a thread.

When I crossed the Allenby Bridge from Jordan to Jerusalem two days ago, the differences after the passing of 15 more years were evident. Where once the bridge crossing was a fairly quiet, restrained affair – Israeli security and immigration checking papers carefully but quickly, orderly queues of chattering travellers moving steadily – now the process and the people gave every sign that I was entering a conflict zone, or at least a place where fear reigned. The first time our UN vehicle was stopped, our passports were checked and we were asked if we were carrying weapons. Then we were led to a large, fortified building where we were taken through x-ray machines and pat-downs. As UN reps, we were given special treatment and taken into a side room for the security check, but there we waited for several hours because one of our party had an American passport and an Arab name.

I was happy to get to Jerusalem and my favourite hotel and even happier to get a room overlooking the Old City – there is surely no more glorious view to wake up to – so the machine guns and fortifications and climate of fear and persecution subsided, but it was temporary. After just one night in Jerusalem, I set out for Ramallah and for the first time saw The Wall.

It has left me shaken but most of all overwhelmingly sad. It is surely not only a wall, barrier, fence, seam – it is an evident obstacle to peace, a negative message to the children of Israel, and a signal to the Palestinians that their hopes and expectations are no nearer to being realised.

Today, I can’t see a solution.